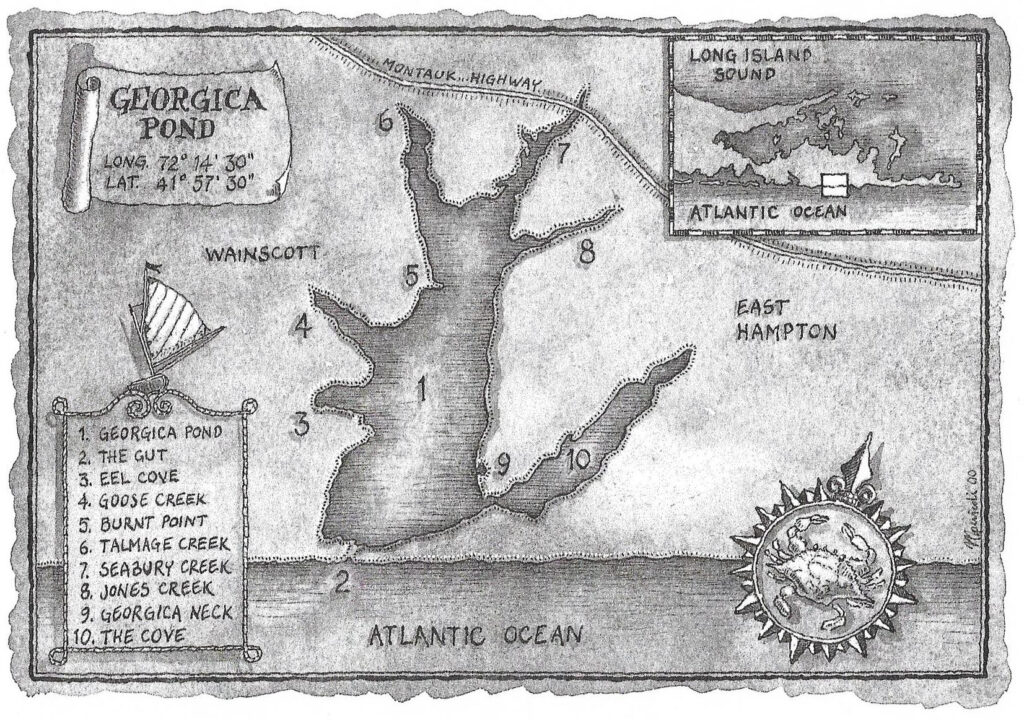

East Hampton has a fascinating history and we are so lucky to have many historical records preserved at places like the Long Island Collection at the East Hampton Library and the East Hampton Historical Society. Although we know less about the pre-colonial Indigenous history, we are learning more. English colonial settlement started around 1639 and its agrarian economy depended on the forests, fertile soils, ponds, and bays that existed in the area. That included Georgica Pond, or as in some early deeds and records it was referred to as “ye pond” or “Georgike.”

By understanding some of the early land use we can better understand the current state of Georgica Pond; what has changed and what has not.

A 21st Century analysis of land use of the 4,000-acre Georgica Pond watershed by the Town of East Hampton estimates that 59% of the watershed is developed, 34% is undeveloped and 7% is water. Looking back at previous centuries, those percentages were very different.

Native Forests

Since the last ice age, forests covered Long Island and most of the Georigica watershed. In a 1717 deed from William Mulford to Joseph Osborn transferring 8 acres of land at Georgica Neck “timber wood, all fancy wood” was referenced. This most likely was oak. By 1773 a nearby parcel of land of 11 acres located at the southernmost end of Georgica Neck was described as “a tract of upland and meadow”. In colonial East Hampton meadow usually meant salt hay (Spartina patens) which grows in salt marshes. At Georgica Pond there is very little salt marsh today. Was there more in 1773?

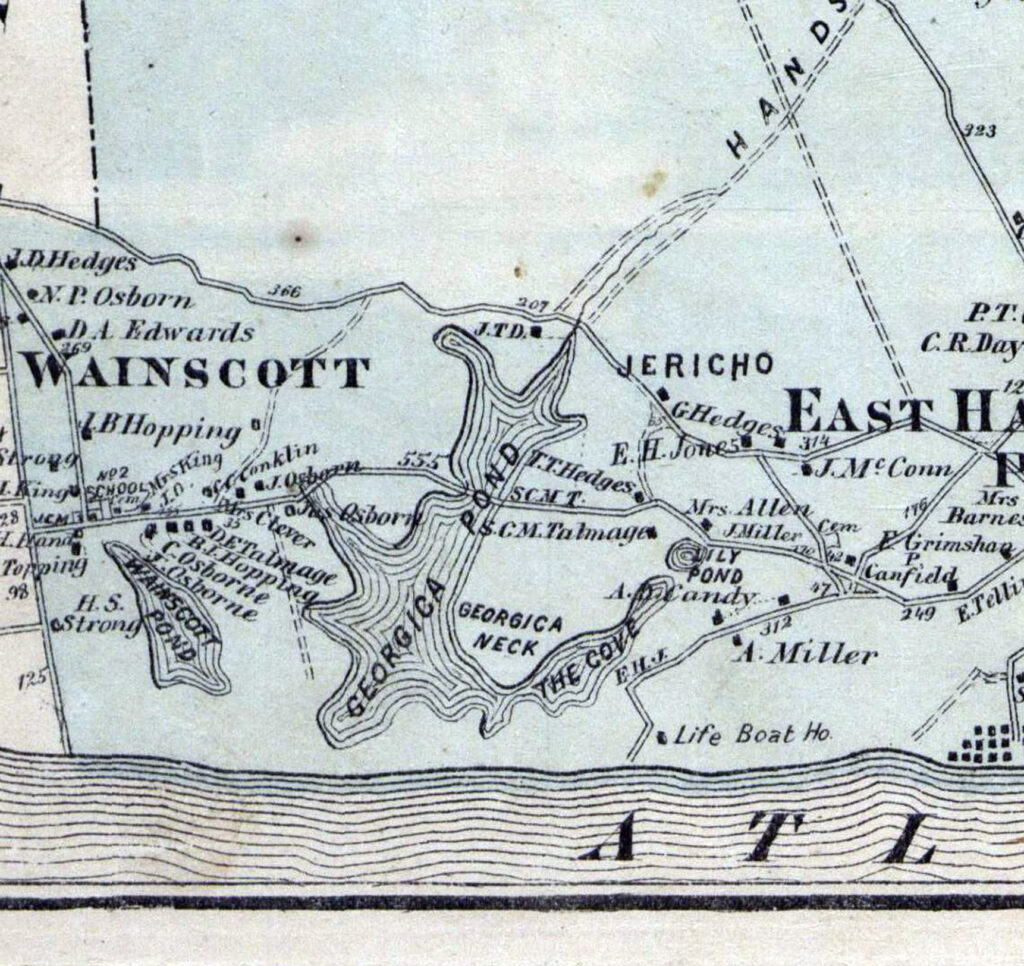

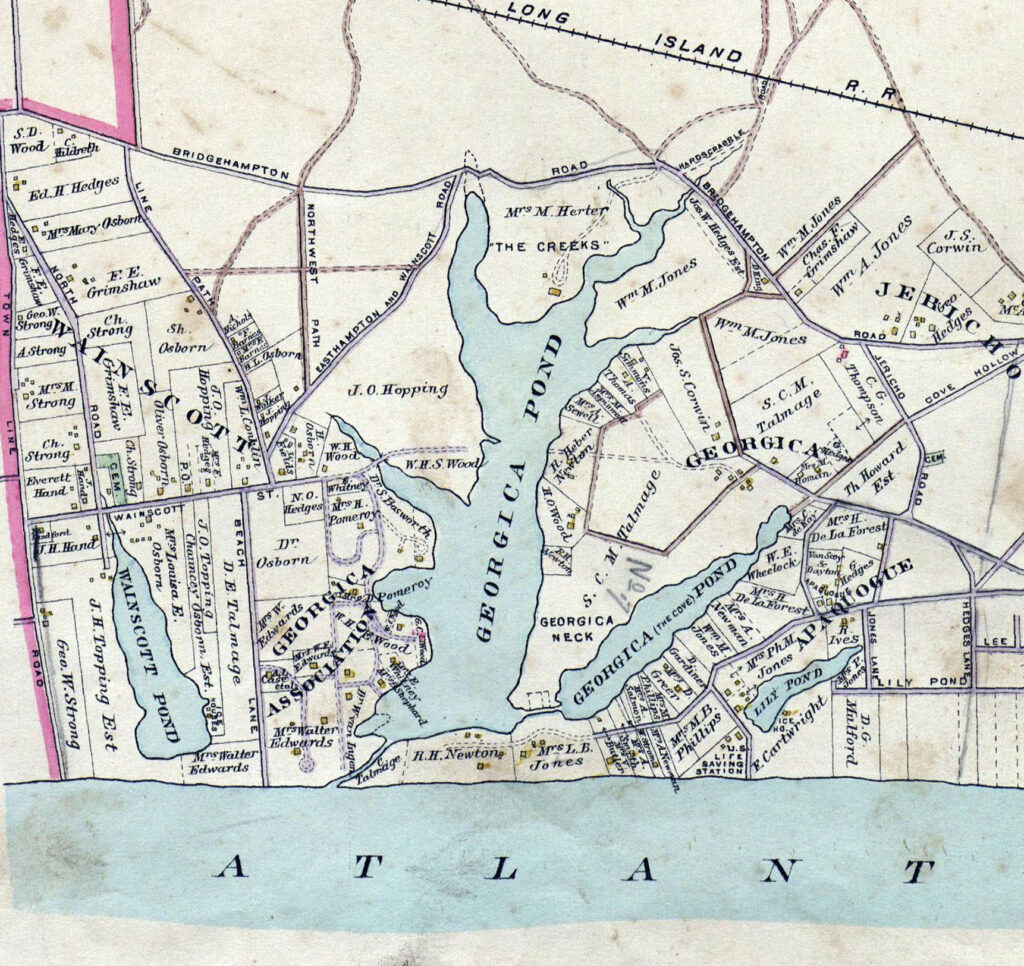

Old Atlas Maps. 1873 versus 1902. What has changed?

What about pine? Today there are acres and acres of pine forest near and north of the pond. Pitch pine forest (and probably white pine too) can also be documented in early deeds. A 1768 deed between Matthew Hedges and Elisha Osborn transferred 36 acres of woodland in “Georgica Pines.” A later deed from 1787 described this same parcel as “lying on the east side (of the pond)… in East Hampton near a place called Georgica Pines.” The “Georgica Pines” place name was still referenced in an 1844 deed. According to architectural historian Bob Hefner, homes of early settlers were framed in oak with sheathing and/or shingles of pine or Atlantic white cedar. There are small remnants of Atlantic white cedar today, but almost all of it is gone.

Cutting the Forest & Plowing the Land

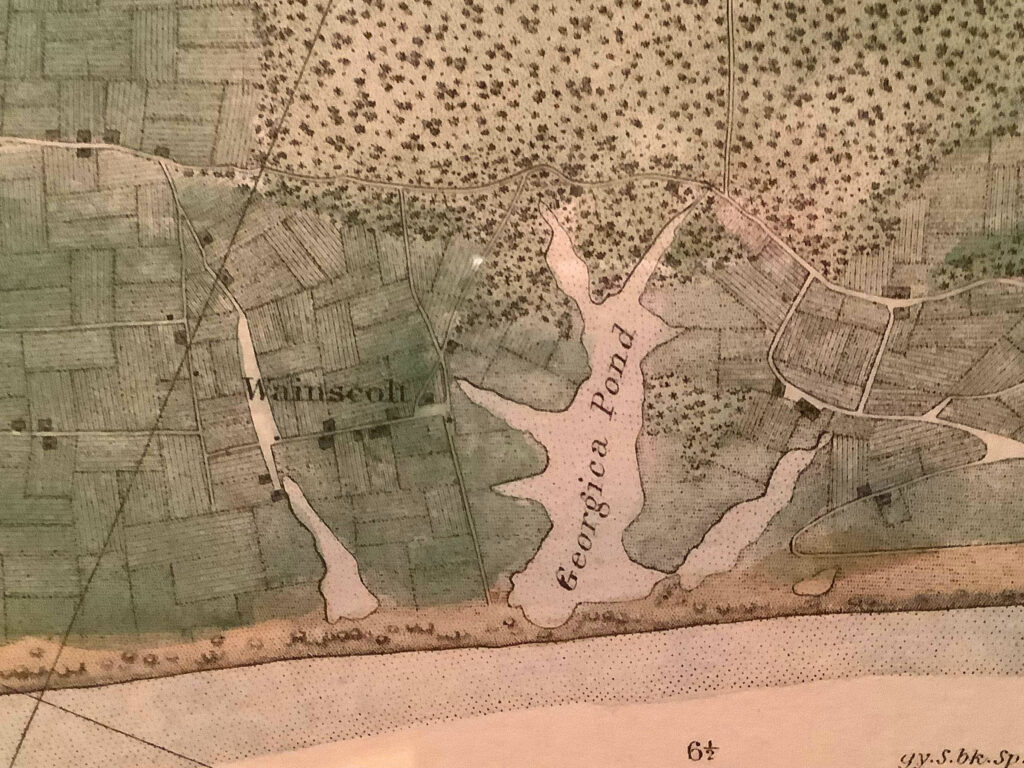

Cutting down trees was hard work but eventually the local supply of trees for timber and fuel grew scarce. The 1806 Hook Mill was built by oak cut from Gardiner’s Island. A 2020 article in the East Hampton Star by David Rattray introduces the Plain Sight Project, and describes the role of Shem, a Black man who sailed to Gardiner’s Island to cut the oak for the Hook Mill. As the native forests were cut down, farming became the dominant land use. An 1857 trigonometrical survey of the coast of the United States overseen by F.R. Hassler shows the vast amount of cleared land near the pond and ocean. This corresponds to the best soils with forest mostly remaining in the north in the sandy soils.

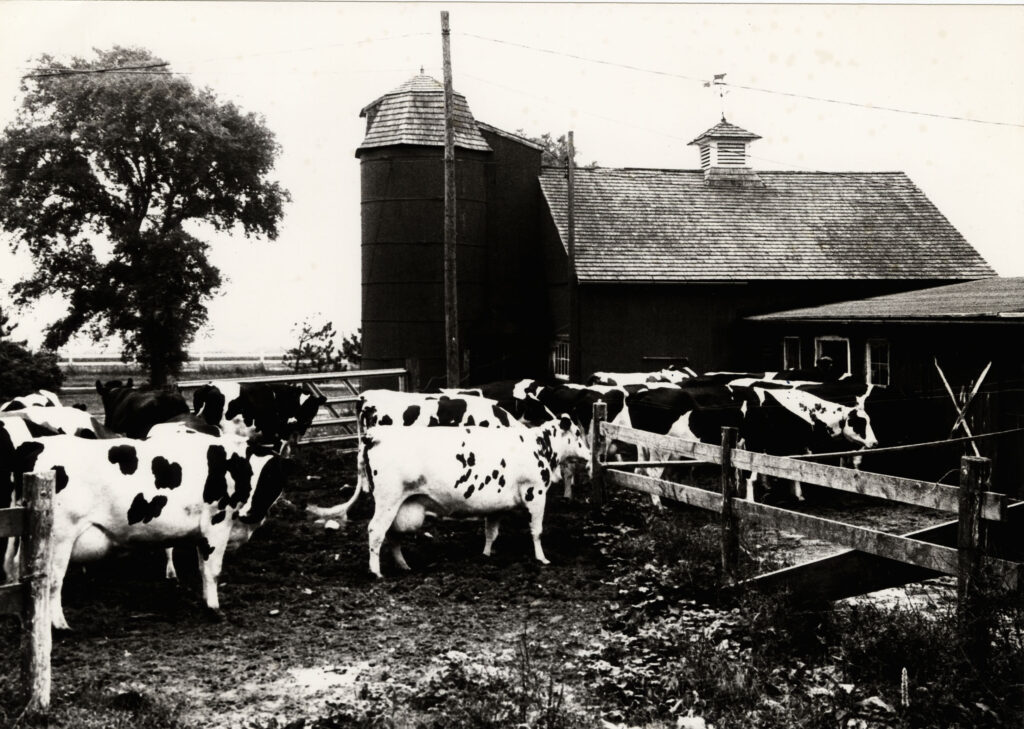

In the 19th Century, most of the landscape was cleared. Local artists depicted bucolic settings of cows wandering down to Georgica and Hook Ponds. Some lovely scenes painted by members of the Moran family and others in East Hampton can be seen at the Gardiner Mill Cottage Gallery on James Lane in East Hampton.

Farming persisted at Georgica Pond at the Cove Hollow Farm Dairy until the late-20th Century. You can still see a silo and other farm buildings on the east side of the pond where the cows once dwelled.

A 1930s era aerial photo clearly shows the open fields north of Georgica Cove where the dairy was and the fields around the former Fulling Mill which today is The Nature Conservancy’s Fulling Mill Farm Preserve.

The wonderfully fertile soil known as Bridgehampton silt loam still supports vegetable farming on the Wainscott side of the pond’s watershed.

The legacy of farming is mixed. Although we don’t have the stone walls that are so common in New England—marker trees, straight ditches, and mounds that once denoted property boundaries—still persist in parts of the landscape. Chemicals, including DDT and its by-products and other agricultural pesticides, can still be found in Georgica Pond’s sediments and excessive nitrogen from fertilizer can cause harmful algal blooms.

Houses Take Over

With the reduction of farming, woodland reappeared in places but mostly residential development took over. Fortunately, much of the zoning for the immediate areas around Georgica Pond is for 5-acre and 3-acre parcels, keeping the house density low. But with 59% of the watershed already developed, there has been a significant loss of natural habitat and contamination of Georgica Pond by runoff and nitrogen enriched groundwater.

Arrival of Invasive Species

Phragmites australis, the common reed grass, and Cygnus olor, the mute swan, were not introduced to Georgica Pond until the 20th century, but they are very common today. These non-native species have altered the landscape and outcompeted some of the native species that thrived at Georgica Pond in earlier centuries.

What vestiges of past century’s land use can you detect at the pond and its watershed? There are many more to be covered in future newsletters.

Special thanks to Andrea Meyer, Director of the East Hampton Library, Long Island Collection, Architectural Historian Bob Hefner, The East Hampton Star, The East Hampton Historical Society, Christine Ganitsch and Terry Wallace at the Gardiner Mill Cottage Gallery.