Four Year Update

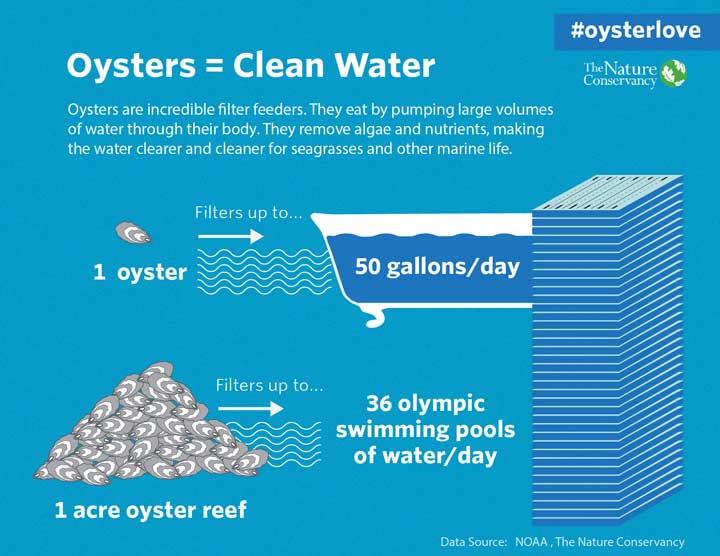

Back in 2019, with the support and urging of FOGP, the Gobler Lab began a trial oyster experiment in Georgica Pond. The goal of the project was to determine if the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) could survive and thrive in Georgica Pond. With their well-documented ability to filter and improve water quality, it was hypothesized that at the right scale, oysters might be able to contribute to the improvement of water quality at Georgica Pond.

Additionally, Mecox Bay, the estuary most similar to Georgica Pond on Long Island is known to host the most abundant population of oysters on Long Island’s south shore.

Still, there were many questions to answer. Would oysters survive the wide fluctuations in salinity and water levels in Georgica Pond? Would Georgica Pond’s abundant blue crab population decimate the oysters?

The experiment to date has consisted of three phases:

Phase 1. Two size classes of individual oysters (first year oysters 14 mm and second year oysters 57 mm) were installed in cages designed to protect them from predators.

Phase 2. Spat on shell. In an ecosystem setting, oysters generally do not exist as individuals like an ‘oyster on the half shell’ but rather exist as colonial organisms, growing in dense assemblages, literally on top of each other, ultimately creating an oyster reef. This happens because when oysters are first spawned, they exist as swimming, microscopic larvae for the first two weeks of their life. After two weeks, larval oysters find a hard surface (usually old oyster shells), undergo a transformation and glue themselves to the old shell. At this stage they are referred to as ”spat.” Clusters of spat on shell were made in the Gobler Lab and were installed with and without cages to determine their growth and survival. This phase included two trials, the first was installing the spat on shell without conditioning them to low salinity water and the second trial conditioned the spat on shell in the lab to low salinity water before installing them in the pond.

Phase 3. Two trial mesoscale oyster reefs composed of shell in mesh bags covered with live oysters (spat-on-shell) were installed at two locations in the pond with hard bottoms.

After four years, the Gobler Lab has found that oysters not only survive, but grow and thrive and even spawn in the pond. A common oyster disease known as Dermo was also scarce due to the lower salinity of the pond. There are signs of crab predation on the oysters as well, particularly on the oyster reefs which will be reconstructed during fall 2023.

Since Georgica Pond is classified as an impaired water body, the goal of this experiment is not to produce oysters for consumption no matter how delicious they are—but rather to assess whether they can be a useful tool in water quality remediation. Oysters can be particularly effective in poorly flushed, small embayments. Thanks to the Gobler Lab’s groundbreaking experiment, we know that oysters can survive in the pond. The jury is still out on whether a self-sustaining reef can be established and the experiment is ongoing. Watch for future updates!

The Georgica Pond oyster project would not be possible without the fine team at the Gobler Lab including Mike Doall, Brooke Morrell and Tim Curtin and the cooperation of the following homeowners: Anna Chapman & Ronald Perelman, Annie & John Hall, Priscilla Rattazzi, Kelly Klein, Jane Overman and David Blinken. In addition, support from the East Hampton Town Trustees, the NYSDEC, and the Town of East Hampton shellfish hatchery was critical to the project’s success.