What is it?

The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is a fascinating fish with a remarkable life cycle. It occupies a very broad range of habitat along the east coast from Central America to Greenland and once made up a quarter of the total fish found in Atlantic coastal streams (United States Fish & Wildlife Service). How could something this widespread and common now be threatened with extinction and have so many questions still remaining about its biology?

Born in the Sargasso Sea

Adult American Eels migrate to the Sargasso Sea—a region in the Atlantic Ocean whose closest landmass is Bermuda—where they spawn. They have never been observed spawning in the wild and the exact location of spawning is unknown. The fertilized eggs hatch into larvae which drift in ocean currents reaching our coastal bays, rivers, and lakes.

Move to Fresh Water

At this point the eel larvae change into tiny clear eels called glass eels. They are called elvers as they grow and add color.

Elvers are athletic swimmers and can climb on rocks in rivers or specialized ramps to allow them to migrate around dams in coastal rivers. Elvers change again into yellow eels and eventually into a silver eel which is the adult stage at about 10-25 years. The silver eels leave coastal freshwater habitats and head to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and die.

Georgica Pond Connection

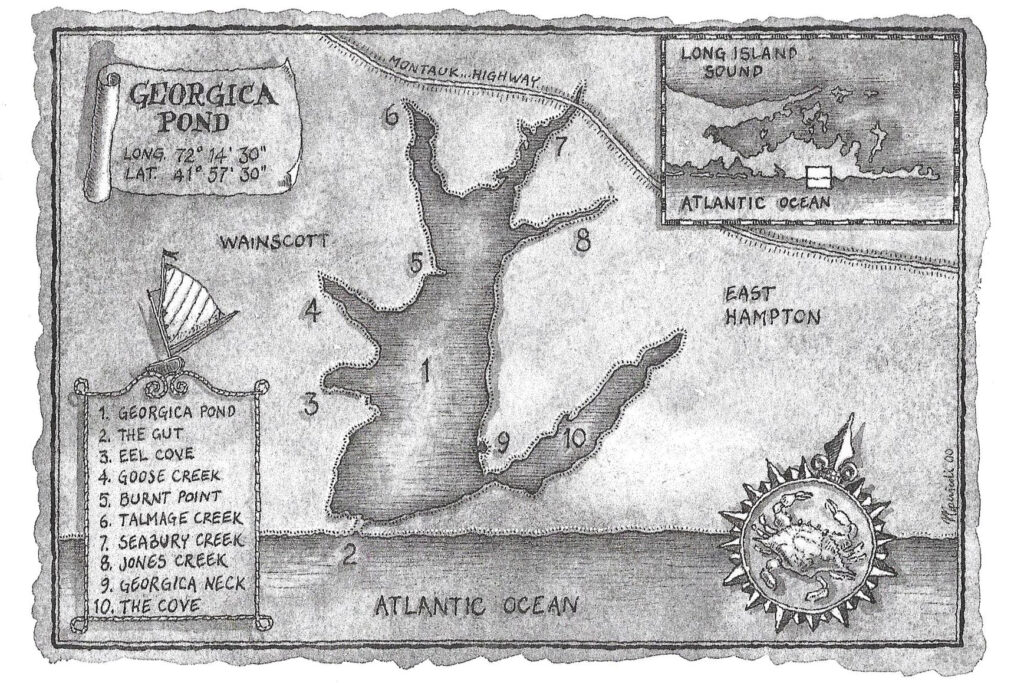

Since Georgica Pond is connected to the ocean at least twice yearly by the East Hampton Town Trustees and by occasional natural openings, the American Eel easily enters the pond. Once in Georgica Pond, the eels mature and, when ready, they seek a quick exit. Like elsewhere, eels were once more common in Georgica Pond. Trustee records show that in 1987-1988 approximately 20,000 pounds of American Eel was harvested from Georgica Pond and at $1.20/pound, represented a total of $24,000 in revenue. Eel Cove on the western shore of Georgica Pond (see map) was no doubt named for the abundance of eels.

Today, elvers are frequently seen and, occasionally, yellow eels are spotted. Local fishermen still catch small eels using an eel pot and use them for bait. A squiggling eel is apparently ideal bait for striped bass.

Threats to the American Eel

The American Eel has been an important part of the US fishery for hundreds of years. Recently, several factors have come together to create a highly uncertain future for the American Eel. Dams, pollution, the glass eel market and changing current patterns due to global warming are all implicated. The International Union for Conservation of Nature ( IUCN) has reported a 50% drop in the total population in the past several decades.

Dams

Many of the rivers used by eels have been dammed. Special structures can be built to allow the eels to swim around dams, but much eel habitat is now inaccessible to them.

Pollution

Eels eat a variety of aquatic life and appear to concentrate some toxins. This year, the Suffolk County Health Department found that American Eels in several south shore rivers including the Carmans River and Quantuck Creek in Quogue had elevated levels of PFAS. They recommended restricting the consumption of eels. PFAS include PFOS and PFOAS; the same emerging contaminant found in Wainscott drinking water. The NYS Department of Health maintains a helpful website “Advice on Eating Fish.” According to the website, eating eel should be restricted to no more than 4 times/month and 1 time/month for young women and children.

Overfishing

The Eel market changed dramatically in 2010 when the EU banned the export of European eels and the 2011 tsunami in Japan wiped out Japanese eel stocks. All of a sudden, the American eel was in huge demand. This “Sushi Crisis” led to a booming trade in glass eels, the beautiful, clear young eels which are harvested by the tens of thousands of pounds and shipped to commercial aquaculture farms in China where they are grown out to adulthood and sold for sushi (Scientific American Dec. 1, 2014). Prices for glass eels reached $3,000/pound and illegal trade in the northeast soared. The US Fish & Wildlife Service staged an undercover crack-down called “Operation Broken Glass” and nineteen eel smugglers were sentenced. Quotas and other limits on glass eels have been instituted, but the problem persists (National Geographic June 27, 2018). According to the NYSDEC, glass eels are illegal to harvest in New York State. In 2018, a member of the Shinnecock Tribe was arrested for catching glass eels claiming early treaties superseded current government regulations (NY Times Feb. 2, 2018).

Global Warming

Possibly one of the most difficult threats to eels is that with the rise in global temperatures, the ocean currents so important to transporting the larval eels to their freshwater habitats, are changing. Whether new ocean current patterns will bring the American Eel to suitable habitat is unknown.

What’s to be done?

It is not impossible for a once highly abundant species to go extinct. The Passenger Pigeon is probably the best example, but this happened long before the endangered species act. The American eel has been reviewed by the USF&W Service twice for listing as a threatened species; once in 2007 and once in 2015. Both times they found the listing wasn’t warranted. The 2015 decision is especially noteworthy in that by then the Japanese eel was endangered and the European eel was critically endangered and the pressure on the American eel by the “Sushi Crisis” was well known (IUCN). The balancing act of managing a commercial fishery versus conservation is always challenging. FOGP recommends that for your own health and to help the species, the next time you eat in a Japanese restaurant, you might wish to avoid the eel.

Special thanks to Dr. Howard Reisman, Ichthyologist; Kevin Miller and Greg Verity for their assistance with this newsletter.